From Paper Scraps to Festival Screens: Shubhavi Arya’s Journey

Welcome Shubhavi, we are very excited to have you today with us to discuss about your work.

Who is Shubhavi Arya and how did the passion for creating begin?

I’m a filmmaker, animator, and educator who works at the intersection of storytelling, psychology, and creative computing. My passion for creating began when I was twelve, after my mother signed me up for a summer animation workshop in Delhi. The short film I made there unexpectedly screened in Serbia, and suddenly the world of independent animation opened up to me. A year later, I traveled to Denmark with my teacher, learning under the Viborg Animation Festival environment and absorbing everything I could about handmade storytelling.

Since then, creating has been less of a choice and more of a rhythm something I’ve carried with me through every stage of my life. I’m drawn to stories that feel intimate yet expansive, especially those told through children’s voices, because they hold a kind of honesty adults often forget. That early start shaped my belief that storytelling can travel anywhere if it's sincere, and that even small, hand-built films can move across borders.

Can you tell us a bit about your previous work?

My earlier films were deeply rooted in childhood imagination and environmental themes. Adventures of Malia, which I completed at sixteen, traveled to over 40 international festivals including Chicago International Film Festival and REDCAT Children’s Film Festival. Before that, my first animation at twelve screened at Viborg Animation Festival in Denmark and at Golden Snail Film Festival in Serbia. I have also directed several live-action short films, with my last one being "Aniyah" which had a successful run at festivals.

Across these projects, I constantly experimented with cutout animation, stop-motion, and mixed digital methods—tools accessible to young artists that still allow for expressive world-building. Beyond filmmaking, I’ve also created multimedia education frameworks that use animation to teach communication, emotion, and identity to children, blending my background in psychology and informatics with creative practice.

My work has evolved, but the essence remains the same: handmade worlds, told with sincerity, powered by imagination.

“What We Imagined” feels like a dream told through a child’s lens. What drew you to bring the voices of two young girls into this story of transformation and belonging?

I’ve always believed that children see the world with a clarity adults often lose. When I began working with the two girls in the workshop, their drawings and unfinished sentences held a sincerity I didn’t want to reshape into something “adult.” Instead, I wanted to preserve the dream logic, the abrupt emotional shifts, the tenderness behind their ideas.

The themes of belonging, starting over, and being brave came directly from them. When one said, “Humans can change,” and the other added, “It’s about what you like,” I knew the heart of the film was already in the room—we just had to translate it into frames.

Bringing their voices forward wasn’t just a creative decision; it was a belief that storytelling can become a space for empowerment. Their imaginations built the world; my role was simply to guide it into cinematic form without losing that delicate authenticity.

CONVERSATION ABOUT: ‘'What We Imagined''

You started your film career at an early age yourself. How did working on “What We Imagined” with such young creators remind you of your own beginnings in animation?

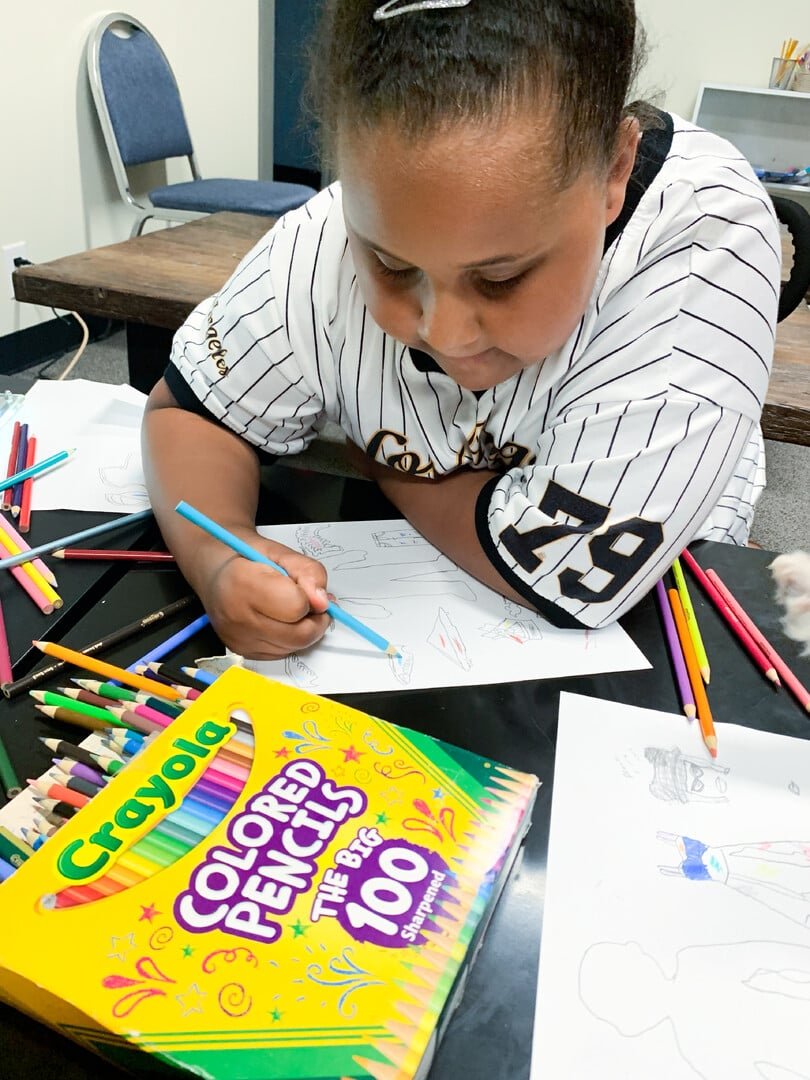

Working with the two young animators felt like holding a mirror up to my twelve-year-old self. I remembered what it was like to sit in a workshop, surrounded by paper scraps, glue, loose ideas, and an adult who believed I could build something meaningful. When the girls came to me with sketches half-formed characters, strange creatures, and quiet observations it reminded me of the raw excitement I felt when I made my first short.

Their process wasn’t linear, and neither was mine when I started. They circled ideas, abandoned some, rediscovered others. They treated mistakes as part of the game. Watching them reminded me that creativity at that age lives in spontaneity, not structure.

It also reminded me of the first time I saw my work screened in Denmark. That feeling of “my imagination is allowed to exist here” was exactly what I wanted them to experience. Seeing their pride when frames began to move felt like giving back a piece of what was given to me when I was their age.

In many ways, What We Imagined wasn’t just their beginning it allowed me to revisit mine with a deeper sense of gratitude.

Was the project more frame-by-frame, cutout-style, or digitally composited — and what were the biggest technical hurdles of that choice?

The film was created through a hybrid approach—stop-motion photography captured with a simple webcam, layered with digital compositing and cutout-style elements. Because the animators were eight and nine, the process had to be tangible yet forgiving.

The biggest hurdle was maintaining consistency. Children animate with enthusiasm, not precision, so spacing, lighting, and movement varied wildly from frame to frame. Instead of correcting everything, we embraced the irregularities and built a compositing workflow that let the “handmade” feel stay alive while still shaping it into a coherent film.

Another challenge was integrating their digital drawings into the stop-motion world, especially the “desktop of dreams” sequence, which required syncing analog and digital aesthetics in a way that still felt childlike.

The imperfections became part of the signature.

What advice would you give to younger filmmakers who may feel intimidated by the challenges of independent cinema?

Start small. Start messy. Start anyway. Independent cinema isn’t about perfection—it’s about persistence. My first films were made with paper, scissors, and a basic camera, but they still traveled to international festivals because they were sincere.

Don’t wait for permission or equipment. Make the film you can make today, not the one you imagine making ten years from now. Surround yourself with people who believe in your ideas, even if it’s just one friend or mentor.

And most importantly, don’t be afraid of mistakes. Your style will emerge from the things you thought were flaws.

In future projects, do you plan to explore similar genre intersections, or are there other genres you're eager to explore ?

I’m drawn to intersections—animation blended with psychology and creative computing, fantasy grounded in realism, stories told through a child’s lens but built with sophisticated emotional frameworks. So yes, I’ll continue exploring magical realism and character-driven animation, especially where it overlaps with identity and transformation.

But I’m also excited to expand into longer-form narratives and experimental digital forms stories that mix animation with live action, behavioral data, or interactive elements. My background in informatics gives me tools to explore storytelling structures that respond to human emotion and behavior in new ways. Genre, for me, is a starting point not a boundary.

If this film could spark one conversation around a dinner table, in a classroom, or even between strangers, what would you hope it would be?

I hope it sparks a conversation about identity not in a heavy-handed way, but in the simple language of the film: you’re allowed to be who you are, even if you’re still figuring it out.

I’d love for families, teachers, or strangers to talk about moments when they felt misunderstood, or moments when they changed, or wished they could. The film is small, but it carries a universal truth about belonging and transformation.

If it helps someone grant themselves or someone else a little more kindness, then it’s done its job.

Mistakes in the story aren’t treated as final judgments, but as stepping stones. How do you see storytelling playing a role in reshaping how society treats failure and growth?

Storytelling has always been a rehearsal space for failure—a place where a character can break, get lost, start again, and still move forward. In What We Imagined, mistakes weren’t erased; they became part of the emotional architecture of the film. Even the computer glitch in the narrative became symbolic rather than something to hide.

I think stories like this allow audiences to reframe failure as movement rather than an endpoint. Children understand this instinctively—they retry, redraw, rebuild without shame. Adults often forget that. Cinema gives us permission to return to that mindset.

When a story shows that imperfection can coexist with beauty, it subtly rewrites how we think about growth in real life.