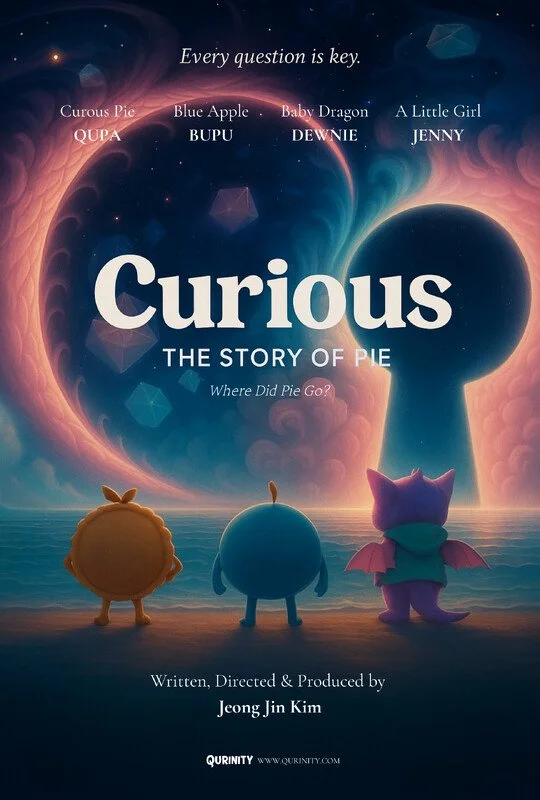

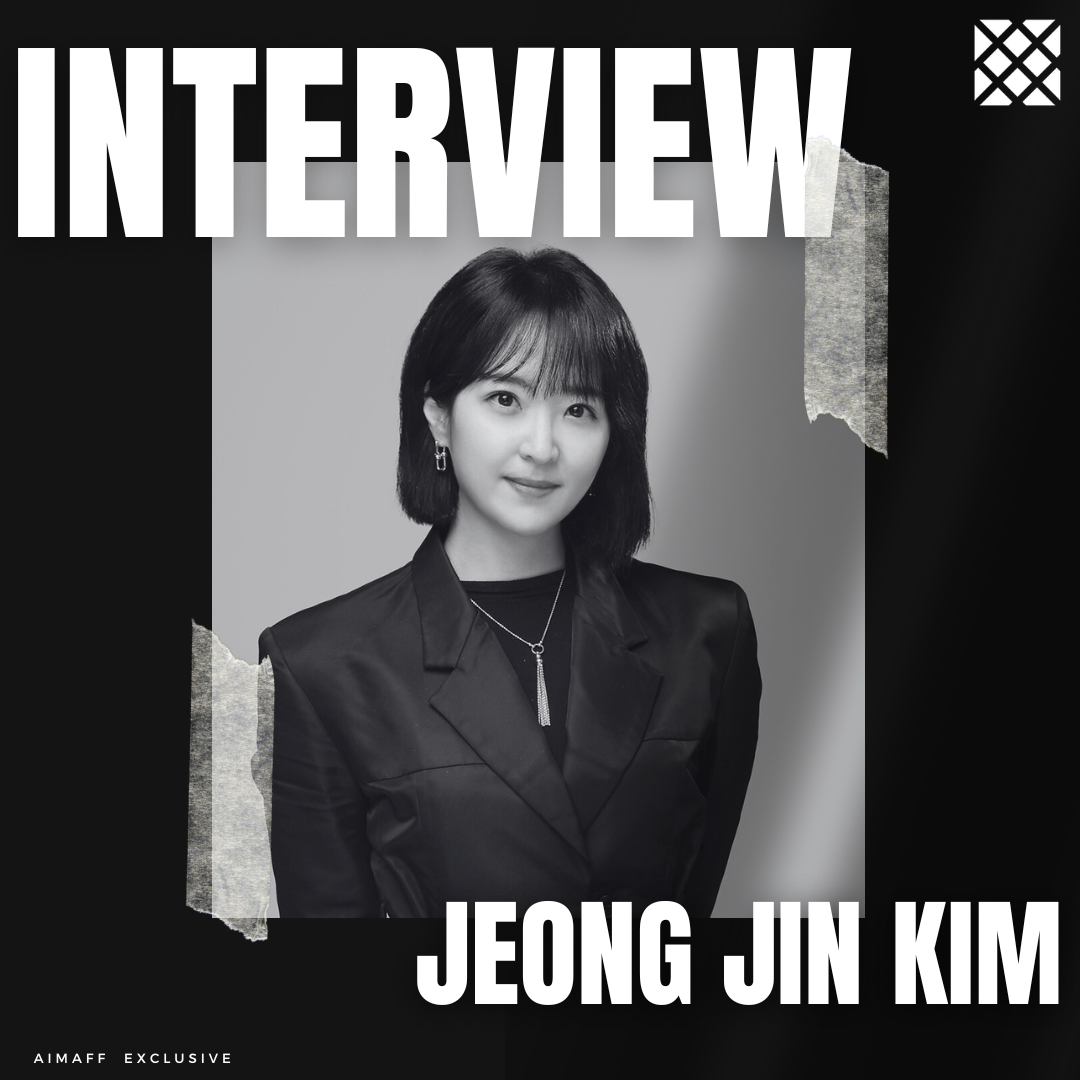

Jeong Jin Kim on Curiosity, Childhood, and ‘The Story of Pie’

Welcome Jeong, we are very excited to have you today with us to discuss about your work.

Who is Jeong Jin Kim and how did the passion for creating begin?

I am Jeong Jin Kim, a storyteller who builds worlds where emotions become characters and questions become places. My passion for creating began long before I ever thought of filmmaking. I studied classical vocal music from 11 years old, and grew up moving between Korea, Sydney, and New York as my family lived across these countries.

Living among different cultures and languages, and being surrounded by artists and designers in my family, I was immersed early on in art as a way of understanding the world. In New York, my love for art led me to volunteer at the Guggenheim Museum’s Visitor Experience department. Being so close to art, people, and stories from around the world deepened my curiosity—not just about art itself, but about the emotions and questions behind it.

As I grew older, that curiosity never left me. It became quieter, layered with responsibility, expectations, and speed. Creating became a way to return to that original state of wonder—to listen to emotions before they are labeled or corrected. I don’t create to give answers. I create to protect questions. Especially the small, fragile ones that tend to disappear as we grow up. Curious (The Story of Pie) is an extension of that lifelong instinct: to ask “what if?” not to escape reality, but to understand it more gently.

Can you tell us a bit about your previous work?

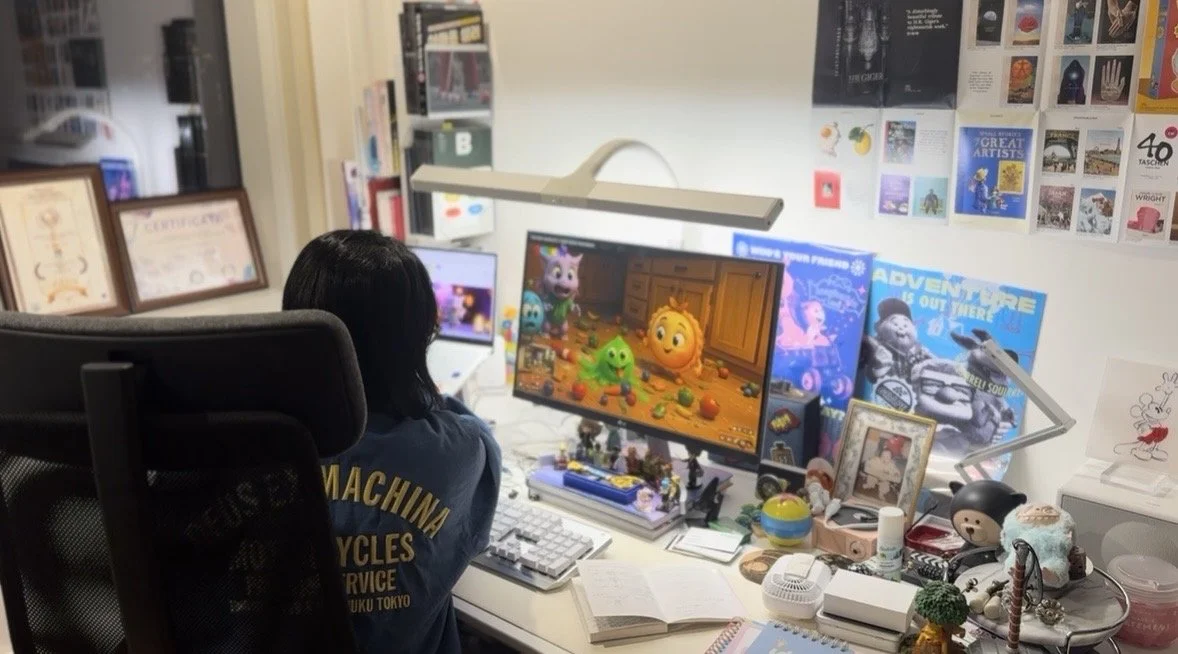

My background is rooted in brand storytelling, creative direction, and emotional narrative design across fashion, lifestyle, and media industries. For over a decade, I worked with global brands, shaping narratives that connect identity, feeling, and meaning. Alongside that professional path, I was quietly building fictional worlds—writing stories, designing characters, and experimenting with visual storytelling. In 2018, I took an early step toward animation by developing an animated project based on my original short story, BBUA the Rice. I collaborated with like-minded artists across San Francisco and Korea, gathering a small, passionate team to bring the story to life. (https://www.bbuatherice.com/) The project had its limitations and challenges, but it was an incredibly fulfilling experience. We presented interactive screenings in cafés and visited kindergartens, where children could engage directly with the animation. Seeing how children responded—how they interacted, asked questions, and emotionally connected—gave me a profound sense of clarity about the kind of work I wanted to pursue. Those early experiments eventually evolved into Qurinity, an original IP universe centered on curiosity, empathy, and emotional growth.

Curious (The Story of Pie) is my first fully realized short film, but it carries years of unseen work behind it—stories once shared quietly, characters waiting for the right form, and questions searching for a voice.

Your film opens with a deceptively simple question: What if curiosity disappeared? When did that question first start haunting you?

That question appeared quietly, not dramatically. I’ve always felt the power of curiosity in my own life. Curiosity has been what led me toward passion, connection, and a deeper understanding of both the world and myself. It has never felt like a weakness to me—it has felt like a compass. Over time, however, I began noticing how often adults apologize for being curious—how curiosity is framed as inefficiency, distraction, or immaturity. At some point, asking “why” becomes something we rush past rather than sit with.

The question truly began haunting me when I realized that curiosity doesn’t disappear suddenly—it fades slowly. Through silence, through the fear of being wrong, through the pressure to already know. As technology and artificial intelligence continue to advance, I found myself asking a deeper question: in a world where answers are instant, what remains essentially human? The answer kept circling back to curiosity—the impulse to wonder before concluding. I began imagining curiosity as something physical. Something that could wander off. Something that could be lost if no one noticed. That was the beginning of The Story of Pie.

CONVERSATION ABOUT: ''Curious (The Story of Pie)''

The Figure Universe feels like a subconscious playground where emotions are born. How did you begin designing a world that represents feelings rather than logic?

I’ve always felt that I live exactly between emotion and reason—almost evenly split. I deeply love art, culture, love, and the wide spectrum of human emotions that often resist explanation. At the same time, I’m fascinated by worlds that are structured, mathematical, and governed by scientific logic—where things can be measured, calculated, and understood. That tension has always felt strangely attractive to me.

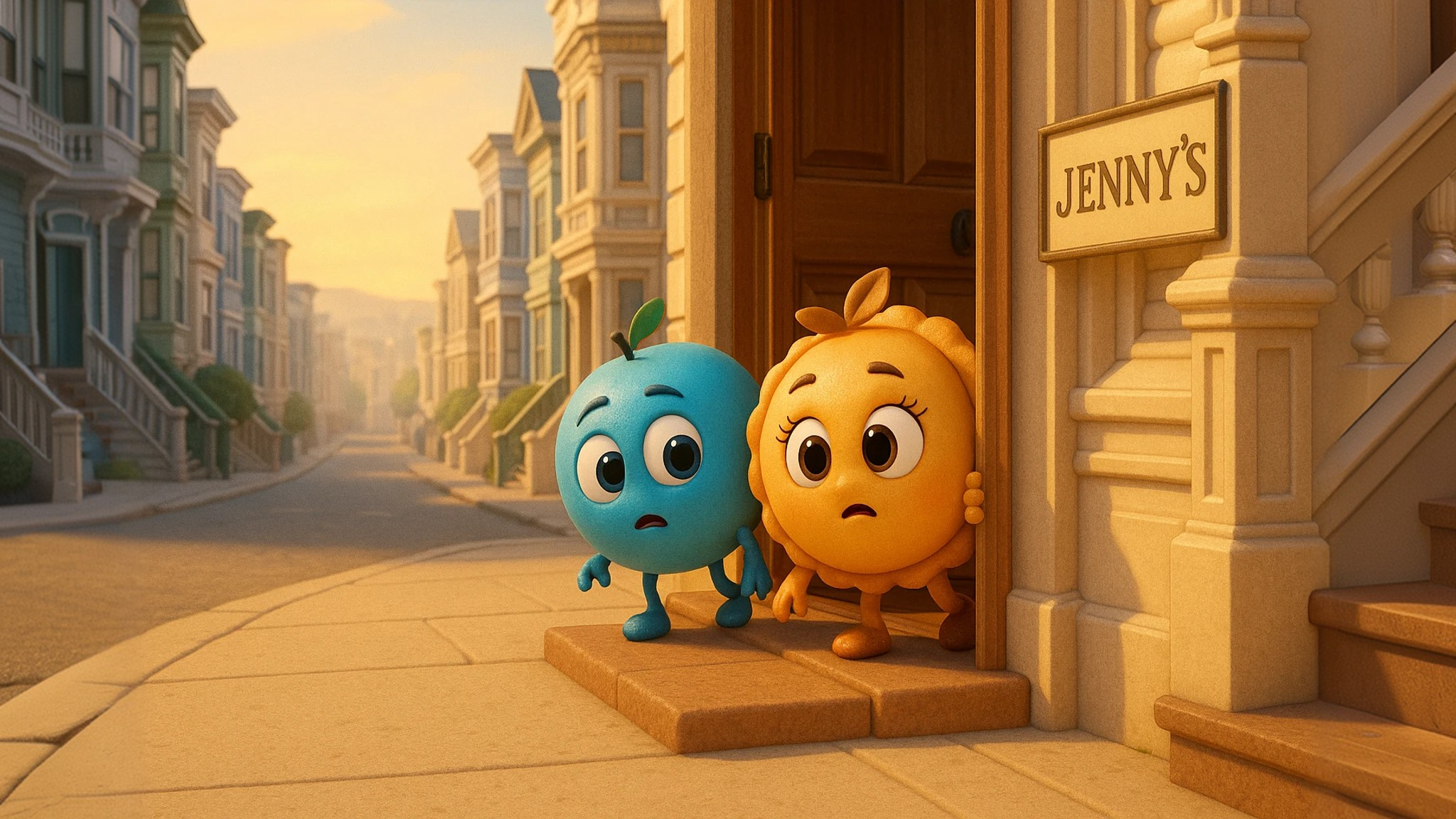

The Figure Universe was born from that collision. On the surface, it resembles a world built from mathematical shapes, geometry, and physical logic—almost like a universe governed by science. But beneath that structure, I wanted to express something far less explainable: the unconscious playground where emotions are born, where human complexity and mystery quietly live. I began by letting go of explanation. Instead of asking “what makes sense,” I asked “what feels familiar?” Emotions don’t follow straight lines—they appear suddenly, overlap, contradict each other. In the Figure Universe, those qualities are normal. Shapes soften, scale shifts, and time feels slightly suspended, like a memory you can’t fully place. I treated emotions as landscapes rather than concepts. Curiosity became something you could bump into, follow, or lose. Fear wasn’t an enemy—it was a shadow that grows when unattended. Rather than building a world ruled by logic, I built one guided by moods—where structure and mystery quietly coexist, reflecting the unexplained beauty at the core of being human.

You chose animation to make abstract ideas feel alive. What freedoms did animation give you that live action never could?

Animation allowed emotions to exist without explanation. In live action, abstraction often demands justification. In animation, it can simply be. I could let a pie feel lonely. Let silence have weight. Let curiosity drift away like a living thing. Animation gave me permission to visualize the invisible—to express internal states without translating them into dialogue or strict realism. It also offered a sense of gentleness that felt essential to the story. Movement could be soft, timing could breathe, and emotions could unfold without urgency. Nothing needed to rush toward a conclusion.

I also believe that even heavy or reflective themes can be approached lightly. Cute, gentle animation has a unique ability to open people’s hearts. When characters feel approachable, audiences lower their guard. They become willing to feel before they analyze. Through animation, I was able to invite viewers into a difficult question without fear or resistance. The softness of the visual language became a doorway—allowing complex emotions and ideas to enter quietly, and stay a little longer.

Was there a moment during animation where the characters surprised you or revealed something unexpected about the story?

Yes—very clearly. That moment came through a character named Tantins, who offers the Pies cookies that provide instant comfort. At first, I imagined Tantins as a clear antagonist, almost a villain—someone who distracts curiosity with easy satisfaction. But as I developed the animation and the story, that certainty began to collapse. I realized that Tantins were not born out of malice. They were born out of need. Their existence made sense in a world where immediate comfort is often chosen over curiosity. What surprised me most was the emotion I felt toward them when their role began to fade. It wasn’t fear or triumph—it was something closer to sadness. A sense of loss. I started asking myself: are they truly evil, or are they simply fulfilling the purpose they were created for? That question stayed with me for a long time.

It became the part of the script I rewrote the most. Through Tantins, the story taught me that there is rarely a “perfect villain.” Sometimes, what we label as harmful is simply something that once served a need—and quietly lost its place.

This is an animated story for children—but it speaks powerfully to adults. Who did you imagine sitting in the audience when you were creating it?

I imagined two people sitting side by side. A child, watching without needing explanation. And an adult, remembering something they didn’t realize they had lost. In many ways, I see myself as an adult who is still a child—and I believe every adult carries a child within them. This story is meant for children, but also for the children living quietly inside grown-ups. The film was made for anyone who once asked questions freely—and then slowly stopped. For parents, creators, thinkers, and children who are growing too fast. For those who still feel something when a question lingers, even if they don’t know how to answer it anymore. I didn’t want to teach or explain. I wanted to gently reflect something back to the audience. Not a lesson—but a mirror, where both children and adults could recognize themselves, side by side.

In future projects, do you plan to explore similar genre intersections, or are there other genres you’re eager to explore?

I plan to continue exploring the intersection of emotional storytelling, animation, and philosophical questions, but across a wider range of tones and genres. I’m particularly drawn to emotional fantasy and poetic, surreal animation—worlds where feelings, memories, and inner conflicts take visual form. At the same time, I’m increasingly interested in gentle, human-centered science fiction, especially as artificial intelligence becomes more present in our lives. Rather than focusing on technology itself, I want to explore what remains essentially human in those futures. Some stories will be lighter and playful, others quieter or more abstract. What connects them is my interest in narratives that sit between children’s imagination and adult reflection—stories that don’t clearly belong to a single genre, but linger emotionally after the screen fades. Curiosity will always remain at the center of my work. The genres may shift, but each world will continue to ask the same underlying question: how do we stay connected to ourselves, and to one another, as we grow?

If you could sum up the film’s core question in a single sentence that would make someone want to watch it immediately, what would it be?

What happens to us when the part of ourselves that asks “why” quietly disappears?